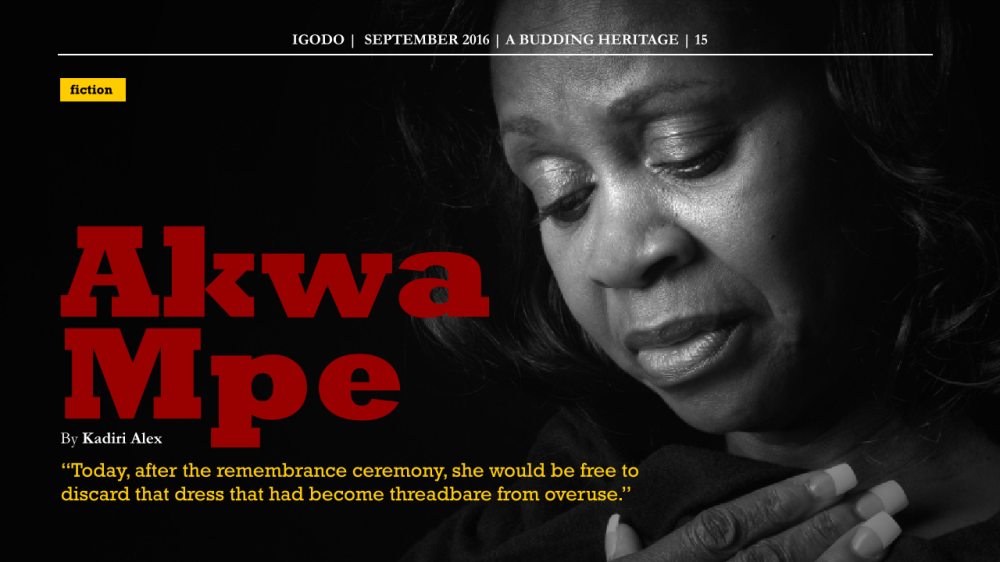

Today was the day Obiageli’s igba mkpe would come to an end. She’d worn that black mourning dress everyday for the past one year since her husband, Osondu, went to bed and slept the deep sleep of death. Today, after the remembrance ceremony, she would be free to discard that dress that had become threadbare from overuse. She would be free, also, from the once unfamiliar smell of mourning that had seeped into the very fibres of that dress so that, soon afterward, she smelled strange, even to herself. And when, eventually, her freedom would be sealed with the casting of the akwa mkpe into the fire, she would watch all the troubles of the past year being engulfed in the flames.

She stood by the small window of the gloomy room to which she had been confined the past year and stared out at the youth as they cleaned the large space in front of the mud house that was her late husband’s homestead. The girls swept the leaves from the udala and cashew trees into a pile and the boys carried the pile with bare hands to the back of the house and dumped them there with all the other decomposing waste. She ran her right hand through her short, tousled hair for a moment and then she scratched and beat against her scalp with the base of her palm. The itch had come again. At first, it had been unbearable, but after a while she’d grown accustomed to it and barely noticed it most of the time. That hair was one of the reasons she earnestly anticipated the ceremony. As soon as it was concluded, she would be free to give it a good combing and plaiting. Clumps had already begun to fall out in places because she’d consistently neglected to care for it – one of the prices she had to pay for Osondu’s death as it was a taboo to wear one’s hair in fashionable patterns during one’s igba mkpe.

When Osondu first died a year ago, she’d been made to kneel before his entire family and although she’d known what they would do to her, she’d been unprepared. The death was still fresh and she had yet to let it all sink in, and there they were, the grim-faced members of Osondu’s family, all gathered outside to watch her head shaved clean while her husband’s corpse lay on a mat inside. Ndubuisi seemed very keen to get on with it and he held the blade menacingly, like a murder weapon. Osondu’s mother sat quietly, grieving and looking very pained with her eyes red and overflowing with tears, and occasionally she would heave her shoulders and scream “a nwuona nu mo!” with a voice so shrill that it penetrated deep into people’s eardrums. The other women of the family consoled her but she didn’t seem to hear and her eyes seemed to look into a distant place and her breaths were punctuated with deep sighs and whimpers. She’d witnessed her husband’s death and now it was her son whom the gods had chosen.

“Ngwanu, set your head well, let Adaku do her duty,” Ndubuisi commanded with an air of importance. He seemed more interested in this inhumane task than he was in grieving for his late elder brother. He passed his wife the blade and for the next ten minutes, Obiageli endured seeing, through teary eyes, the tufts of her hair fall past her face and mix with the dusty red earth. Her scalp felt sore when Adaku had finished shaving it and she dreaded looking in the mirror because she knew it would be bruised and ugly, unlike before when her hair had been her crowning glory and women had asked what herbs she concocted to make it so full and thick. She raised her head for a moment and her eyes caught her younger sister’s in the crowd of spectators. Those eyes seemed to speak to her; they seemed to say I told you so. And if those were the words her sister meant to communicate to her, she deserved every bit of it. When she had talked about marrying Osondu a few years before, Nkechi had been apprehensive.

“Ehn?! Sister, don’t try it o. You want to marry an Umudike man. Haven’t you heard what they do to their widows?”

“Tufiakwa!” She’d retorted, encircling her head with her palm and then snapping her fingers afterward to effectively reject the notion. “The gods forbid it. My own husband will not die before me, biko. Why do you always have to be so negative with your thoughts?”

“Sister, I am telling you what those people do and you are saying tufiakwa. See, sister, those people are too primitive. Besides, what is so special about this your Osondu? Someone that is as short as those cassava plants.”

They burst out laughing and when they’d exhausted all the mirth that their lithe frames could contain, Obiageli clapped her hands in Nkechi’s face and told her: “Imela. Thank you for your advice, eh. But, biko, just leave him for me. Haven’t you heard that short men are very good in bed. Their things are always stubby and they know how to perform well with them.”

And now, Nkechi’s risible utterances on that day might as well have been a premonition. Her world had collapsed and the rubbles were still being pulverized. She wanted to weep, but her fountain had already run dry and her voice hoarse from weeping throughout that morning. Ndubuisi cleared his throat in preparation to address the other members of his family who were all drowned in their sorrow and shaking their heads pitifully.

“My people,” he began, “when a young, agile man like my brother, Osondu, goes to bed and does not wake up for no reason at all, there is something behind it.”

Some of the men nodded their consent and others merely grunted and waited to hear what Ndubuisi was driving at.

“You see this woman,” he continued, pointing a scaly forefinger at her, “Yes! This woman, Obiageli. I’ve always suspected her of mischief. She has other lovers…”

“Ewuo!” Obiageli screamed, her face transforming into a mask of horror. “What are you saying, Ndubuisi?”

“Mechie onu there!” an angry voice bellowed from the crowd.

“Yes. Let him speak,” another chipped in.

“This woman is evil,” Ndubuisi continued. “But, all the same, I don’t want to dwell on that matter. All I want to say is that I have asked them to wash Osondu’s body so that she will drink his mmili ozu to prove her innocence. Ngwanu, Adaku, go and bring it.”

Adaku strutted indoors and returned with the old plastic cup that contained the dreaded mmili ozu.

“Were iko,” she said and thrust the cup at Obiageli.

As much as she’d loved her husband, it was horrifying to even think of drinking the water that had cleaned his corpse, but refusing to do so was tantamount to admitting guilt and so she downed the dirty water in one quick, painful gulp after many long minutes of staring at it. She wanted to vent her anger at Ndubuisi, to undress and stand naked and curse him because she knew all of this was the vindictive man’s payback. He was bitter because of all that had transpired several months back when Osondu had spoken sternly to him as he warned him to keep away from his room and its vicinity. She’d reported Ndubuisi to Osondu because the man constantly kept watch for when Osondu would go out to the farm or to drink palmwine with Obierika. And when he saw that Obiageli was alone in her room, he would sneak over and say the same abominable things about him.

“Osondu is not a man. He cannot put his seed in you because he has sown all of it with every loose woman in this village. Let me give you children. Do you think three miscarriages is a normal thing. Your husband is weak. Let me…”

“Ndubuisi, biko, leave my room,” she would snap. “Please, just get out.”

Things continued in this manner until she could stomach it no longer and she divulged everything to Osondu. The usually taciturn Osondu had called Ndubuisi out and warned him severely, shaking his forefinger in his face, and because Ndubuisi had been penitent, Osondu hadn’t involved the other members of his family.

* * *

Through the window, Obiageli saw Ogbuefi Ezeudu approaching now, the little boy who carried his stool walking a few paces ahead, and she knew that the ceremony would soon begin. She could see some other people behind him too and so she moved away from the window and lay idle on the hard bamboo bed, until Adaku’s scream rent the air. She ignored it. Adaku had been mean to her all this time. Her only friends had been widows like herself who’d visited and offered a few kind words.

She remained on the bed until she heard Adaku’s piercing cry again: “Ndubuisi, a nwuona o!”

GLOSSARY

(1) Igba mkpe – mourning

(2) Akwa mkpe – mourning dress

(3) Mechie onu – shut up

(4) Mmili ozu – the bathwater of a corpse

(5) Were Iko – take the cup

(6) A nwuona nu mo – I am dead

(7) Ndubuisi, a nwuona o – Ndubuisi is dead

This story was featured in a cultural/literary magazine titled Igodo Umuavulu.

Find the PDF file here or visit www.wordsarework.com

This is just…. Beautiful and captivating…. It is brilliant, Alex

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Irene.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a brilliant piece of literature. I love the original and ethereal feel to it, as well as the infusion of a different language, that situates the reader as a distant observer throughout. I could almost hear the last scream in my head. Well Done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Those words mean a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you call my writing beautiful, then I am sure you get your words from heaven. This is awesome.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmmm… Someone’s being nice. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Nigerian Writers Hub.

LikeLiked by 1 person